Charles Dickens (7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870)

This year, 2020, marks the 150th anniversary of the death of one of Britain’s most famous authors: Charles John Huffam Dickens. Born in Portsmouth on 7 February 1812, Dickens moved to Chatham in Kent while he was still young for his father’s work as a pay office clerk for the Royal Navy. From the age of 10, he lived in London and later Kent.

However, Dickens had reason to visit Liverpool many times during his adult life as a writer, actor and public reader, and was inspired and influenced by his visits to the city. In fact, he mentioned Liverpool in his novels more times than anywhere else outside of London, as reported in the Liverpool Echo.

More specifically, he had a particular fondness for St George’s Hall, describing it as “our old friend” and declaring it to be, according to his tour manager, George Dolby, “The most perfect hall in the world”.

In this series of blogs, City Halls guide, James O’Keeffe, explores Charles Dickens’s links to St George’s Hall…

The Goldsmith, the Artist and Charles Dickens

In the summer of 1859, Dickens was one of many visitors to the excavation of the important Roman site, Viriconium (at one time the fourth largest city in Roman Britain), at Wroxeter in Shropshire. The site itself was at that time farmland where turnips were normally grown. In the report of his visit in the journal All The Year Round, Dickens noted that the tenant farmer of the land, which was being excavated, was unimpressed by the interference that this excavation caused with his work: “He would not take all Rome for his turnips!”. The farmer attempted to drive the archaeologists off the field. The antiquary who was overseeing the excavation, Thomas Wright, complained to his financial-backer, Joseph Mayer, about this “abominable tenant”, who was causing so much disruption to the planned excavation. Wright said he wished that the farmer would be “crammed with turnips till he burst!”.

Joseph Mayer (1803-1886)

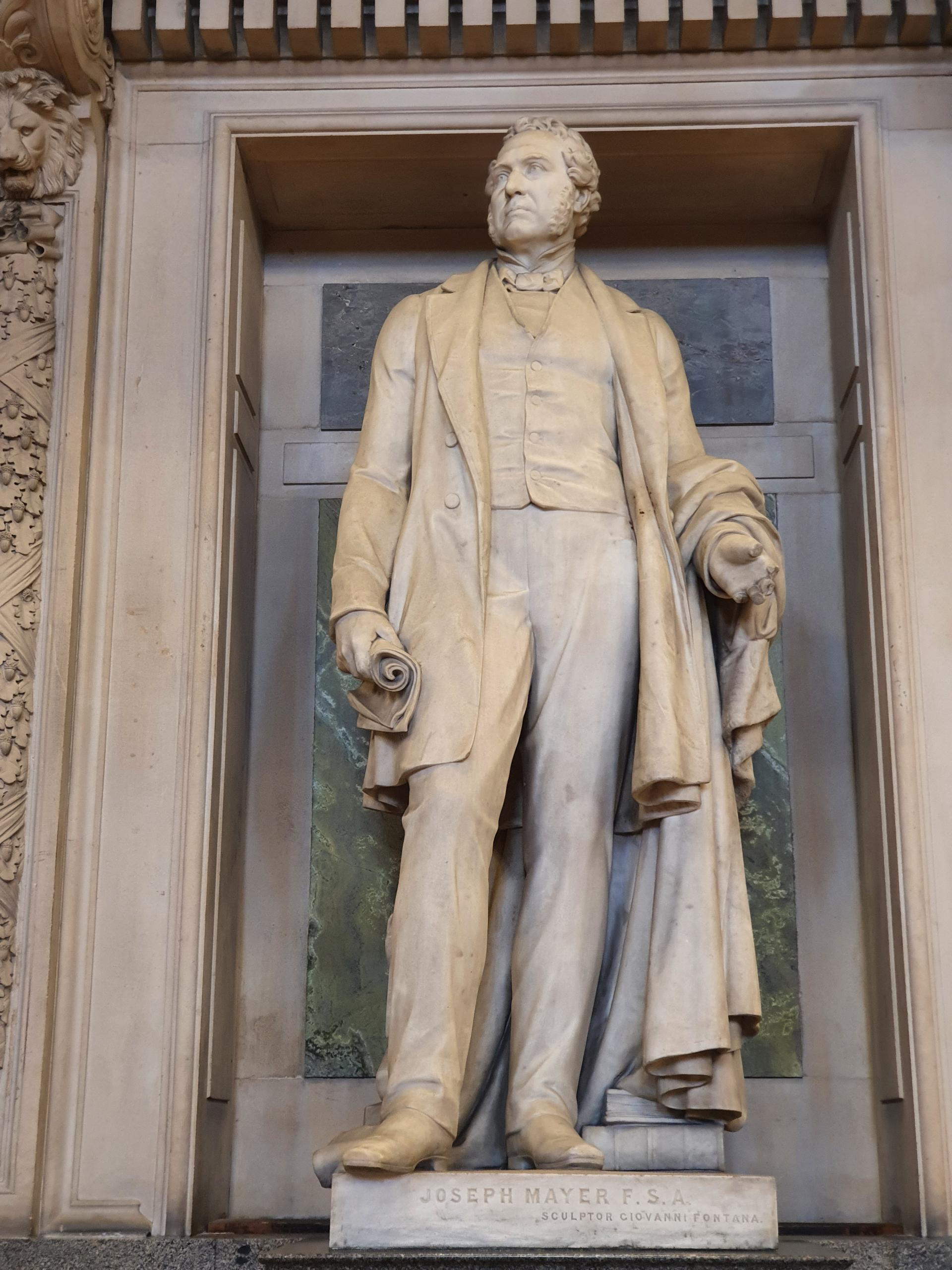

By this link through the site at Wroxeter, we find another connection between Charles Dickens and St George’s Hall: Joseph Mayer. Joseph Mayer (1803-1886) was a successful goldsmith, jeweller, philanthropist and antiquary, based here in Liverpool and also at Bebington. He is remembered in St George’s Hall through one of the thirteen marble statues in the Great Hall.

Born in Newcastle, Staffordshire, Mayer moved to Liverpool in 1821 to work as an apprentice for his jeweller brother-in-law, James Wordley. The pair initially went into partnership together, and in 1844, Mayer set up his own jewellery and goldsmith business in the town at 68 Lord Street.

Mayer proved to be a very successful businessman and his work was extremely popular. He was even commissioned to produce the medal that was presented to official guests at the opening of St George’s Hall in September 1854. His business acumen enabled him to fund his lifelong passion; collecting antiquities. Throughout his lifetime, Mayer, often through extensive travelling, amassed a vast collection of Ancient Egyptian, Roman and Saxon artefacts, as well as ancient and medieval art. He also acted as a patron for historians such as Thomas Wright. Additionally, he funded Wright to be able to produce two books; Anglo Saxon and Old English Vocabularies (1857 and 1873) and Feudal Manuals of English History.

Keen to share his knowledge and collection with the public, Mayer went on to open a museum in Colquitt Street, Liverpool, in 1852: The Egyptian Museum. Here, scholars and fascinated members of the public alike would be able to observe Mayer’s ever-growing valuable collection. By 1867, the museum had amassed more than 15,000 items valued at £75,000. Mayer decided to donate the entirety of the museum collection to the newly opened Liverpool Free Library and Museum, now known as World Museum Liverpool.

Among the art works that Joseph Mayer donated to the museum were some more contemporary paintings by a Liverpool-based artist called Sarah Biffin (1784-1850), who specialised as a miniaturist. Biffin was born in East Quantoxhead, Somerset and travelled widely across the country, living in London, Cheltenham and Brighton before finally settling in Liverpool in 1841. Here, she remained until her death in 1850. During her time in Liverpool she worked from a studio in Bold Street.

A drawing of Sarah Biffin by Margarita Alba, based on a lithograph in the Hornby Library!

What made Sarah Biffin so well-known at the time was the fact that she was born without arms and legs, suffering from the condition phocomelia. However, it was through her skills and great talent as an artist that she earned the patronage of many wealthy individuals including royalty such as George III, George IV, William IV and Victoria, as well as the King of Holland, and her work was hung in the Royal Academy. To paint, she held the brush in her mouth and she could even work a needle with her tongue.

The reason why she travelled so widely when she was young was because she joined a travelling showman, named Emmanuel Dukes, at the age of thirteen. Dukes included Biffin as one of his performers. In 1808, the 16thEarl of Morton (1761–1827) had his portrait painted by Biffin and he was so impressed with the result that he showed it to King George III, winning the king’s favour for the artist. Although she happily continued working for Emmanuel Dukes until 1815, her reputation as an artist grew and, in 1819, Biffin opened her own studio in the Strand, London, specializing in miniatures.

As well as patronage of royalty and local notables such as Joseph Mayer, Biffin’s skills as an artist drew the attention of Charles Dickens, who referred to her in a number of his novels in the 1830s and 1840s.

Dickens wrote of Biffin in Nicholas Nickleby: ‘“The Prince Regent was proud of his legs, and so was Daniel Lambert, who was also a fat man; he was proud of his legs. So was Miss Biffin: she was – no…”, added Mrs. Nickleby, correcting herself, “I think she had only toes, but the principle is the same”’.

He also refers, in The Old Curiosity Shop (1840), to an entertainer who was “a little lady without legs or arms,” which is likely another reference to Biffin.

In Martin Chuzzlewit (1843), the character Mr Pip says that feet are mentioned a lot in Shakespeare’s verse, ‘“but there an’t any legs worth mentioning in Shakspeare’s plays, are there, Pip? Juliet, Desdemona, Lady Macbeth, and all the rest of ’em, whatever their names are, might as well have no legs at all, for anything the audience know about it, Pip. Why, in that respect they’re all Miss Biffins to the audience, Pip”’.

In Little Dorrit (1855), he wrote: ‘Mr Merdle came creeping in with not much more appearance of arms in his sleeves than if he had been the twin brother of Miss Biffin’. In his journal Household Words(1858), Dickens wrote again ‘Miss Biffen with neither arms nor legs worth mentioning’.

Clearly Dickens had a lasting fascination with Sarah Biffin.

Despite initial success, Biffin’s fortunes seemingly changed for the worse. Finding herself in hard financial times, in 1847, Richard Rathbone (1788-1860), the uncle of William Rathbone VI, whose statue is in St John’s Gardens just next to St George’s Hall, created a fund to support Sarah Biffin in her old age. Rathbone actually wrote directly to Dickens, undoubtedly aware of his interest/ fascination in the artist, to appeal to him for a donation, but Dickens replied that he would not be able to contribute anything at all, which seems a little unfair considering the many references he made about her in his popular novels.

Biffin died in 1850, aged 66, at her lodgings in 8 Duke Street and was buried at St James’s Cemetery. Among the collection of the Hornby Library in Liverpool’s Central Library are the engravings of two self-portraits, along with her letters to Joseph Mayer confirming their close connection and his keen admiration of Biffin’s work. The Walker Art Gallery also has in its permanent collection an oil painting, the ‘Portrait of Fanny Maria Pearson’ and two water colours: ‘Portrait of an Elderly Lady’ and ‘Still Life with a vase of Flowers on a Pedestal’. Unfortunately, at the time of writing, none of these paintings are currently on display.

Duke Street, where Sarah Biffin had lodgings.

Joseph Mayer, Sarah Biffin and Charles Dickens come together at St George’s Hall through Liverpool’s farewell banquet held in honour of the writer in the Great Hall on Saturday 10 April 1869. Mayer, due to his good standing in the community, was one of the 650 invited guests at the banquet which Dickens, of course, attended. Whether the goldsmith and Dickens actually spoke to one another, and if they did, whether Sarah Biffin would have been mentioned is unclear, but the evening left a lasting impression on Mayer. He commissioned his favourite sculptor, Giovanni Giuseppe Fontana, to produce a bust of Charles Dickens. He sent a letter to Dickens to invite him for a sitting with the sculptor, but Dickens declined the invitation. Nevertheless Fontana completed his commission and an 1872 version of the bust is on display in the Walker Art Gallery, alongside a number of other sculptures that Mayer commissioned of his friends, including a bust of Thomas Wright.

Also, from 1860, Joseph Mayer had lived in Bebington. His residence was named Pennant House in honour of Thomas Pennant, who was a naturalist and traveller. As well as bringing gas and water provision to Bebington, Mayer donated to the village a Free Library with an excellent stock of books, along with a lecture hall and art gallery in 1869. The parkland surrounding the library was also a gift from Mayer and, after attending Dickens’s Farewell Banquet at St George’s Hall, he renamed the main path through the park ‘Dickens Avenue’. To this day, the park is known as Mayer Park.

Dickens Avenue, Mayer Park.

The statue of Joseph Mayer in St George’s Hall’s Great Hall was unveiled on the same day as the statue of the 14thEarl of Derby by the Mayor Thomas Dover. A coincidence occurs here again as the 14thEarl of Derby had a link to Charles Dickens, as described in this previous blog.

Joseph Mayer was invited by the council to select a sculptor himself to carry out the work. Mayer chose Giovanni Fontana, who was clearly a favourite of his. There are a few features of this statue that are worthy of note. Firstly, the scroll that he holds in his right hand denotes the benevolent gift to Liverpool of his antiquities and art collection. The books at the base of the statue are a reference to his creation of the Free Library in Bebington.

The books at the base of the John Mayer statue at St George’s Hall.

The small Ancient Egyptian statue, just behind Mayer’s right leg, symbolizes the many ancient artefacts that Mayer included in his gift to Liverpool, and provides a link to the nature of the early days of his museum at Colquitt Street, when it was referred to as the Egyptian Museum (the statue that this sculpture is based on was one of Mayer’s pieces which he presented).

The small Ancient Egyptian statue, which forms part of the John Mayer statue at St George’s Hall.

Its original was a votive made for the tomb of Nebamun and was part of Mayer’s collection. Sadly, the Liverpool Museum was very badly damaged in the Second World War, during the May Blitz of 1941. Many original artefacts were destroyed by the bombing raids including the votive that is represented in this statue.

Damage to fingers on John Mayer’s statue.

Remaining on the subject of John Mayer’s statue, it’s worthy to note damage to the statue’s fingers. It’s said that the damage to the fingers happened in the 1960s when the Hall was used for parties and music festivals. Alan Bennett wrote about his experience of the Great Hall during the filming of his story The Insurance Man in 1986: ‘Ranged round the vast hall are statues of worthies from the great days of the city and on the rich floor, a rich and elaborate mosaic, set with biblical homilies “By thee kings reign and princes decree justice”, say the roundels on the floor. “Save the NHS. Keep Contractors Out”, say the other roundels, badges stuck there at a recent People’s Festival … Peel and George Stephenson look down’.

The Blue Plaque at Pennant House, which is in recognition of Joseph Mayer.

Pennant House still exists and is one of a very small number of buildings outside of London to bear a Blue Plaque – in recognition of the significance of Joseph Mayer. His name is also remembered locally through Mayer Park and the Joseph Mayer Trust, which is a charity based in Bebington that provides a series of free lectures annually.

Sources

- Alan Bennett Alan Bennett Plays 2: Kafka’s Dick; Insurance Man; Old Country; Englishman Abroad; Question of Attribution (2009)

- Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby (1839)

- Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop (1841)

- Charles Dickens Martin Chuzzlewit (1844)

- Charles Dickens Little Dorritt (1857)

- Charles Dickens, “Rome and Turnips” in All the Year Roundpp. 53-58, vol. 1, 1858

- Charles Dickens, Reprinted Pieces (1858)

- P Barker The Baths Basilica: Excavations 1966-1990 (1999)

- Terry Kavanagh, Public Sculpture of Liverpool (1997)

- Winifred Leybourne, “Sarah Biffin, Miniaturist” in The Dickensian, pp.165-184, vol. 93, 1997

- Richard Whittington-Egan Liverpool Characters and Eccentrics (1989)

- www.greenflagaward.org.uk/park-summary/?park=2549

- www.themayertrust.org.uk/joseph.html?LMCL=dpAyS5

- www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/stories/forensic-egyptologists-examine-our-mummy

ABOUT JAMES O’KEEFFE

James works as one of the official guides of Liverpool’s City Halls. He has worked in his role for 12 years and delivers a wide range of tours in St George’s Hall and Liverpool Town Hall, including the monthly guided tours, St George’s Hall Film tours, Footman tours and the special ‘Walk the Floor’ tours during the Minton Floor Reveal.

He also helps to animate events in the buildings including the traditional Toasting of the Haggis at the Burns Night Ceilidh and Dickens Readings in St George’s Hall’s Concert Room.

With a Master’s Degree in History, James’s passion is British history with a particular interest in all things Liverpool.